Nurulain Nabihah talks about her experience dancing Indu’ Bantang and subsequently reflects on the role of women in society.

RESTAR ‘20, or Resital Akhir Tari (Final Dance Recital), was a practical course that required the final year students of the Diploma in Dance programme to design, coordinate, demonstrate and structure a dance performance. The final project’s implementation, a group performance, was conducted by the students themselves. I performed in Indu’ Bantang,choreographed by Albert Sigan Saliman. The dance was inspired by indu’ bantang, traditionally the highest position among Ibanic women. Albert wanted to choreograph this piece because the indu’ bantang does not exist today—he wanted to revive his culture and to show respect to his late grandmother, who was an indu’ bantang herself.

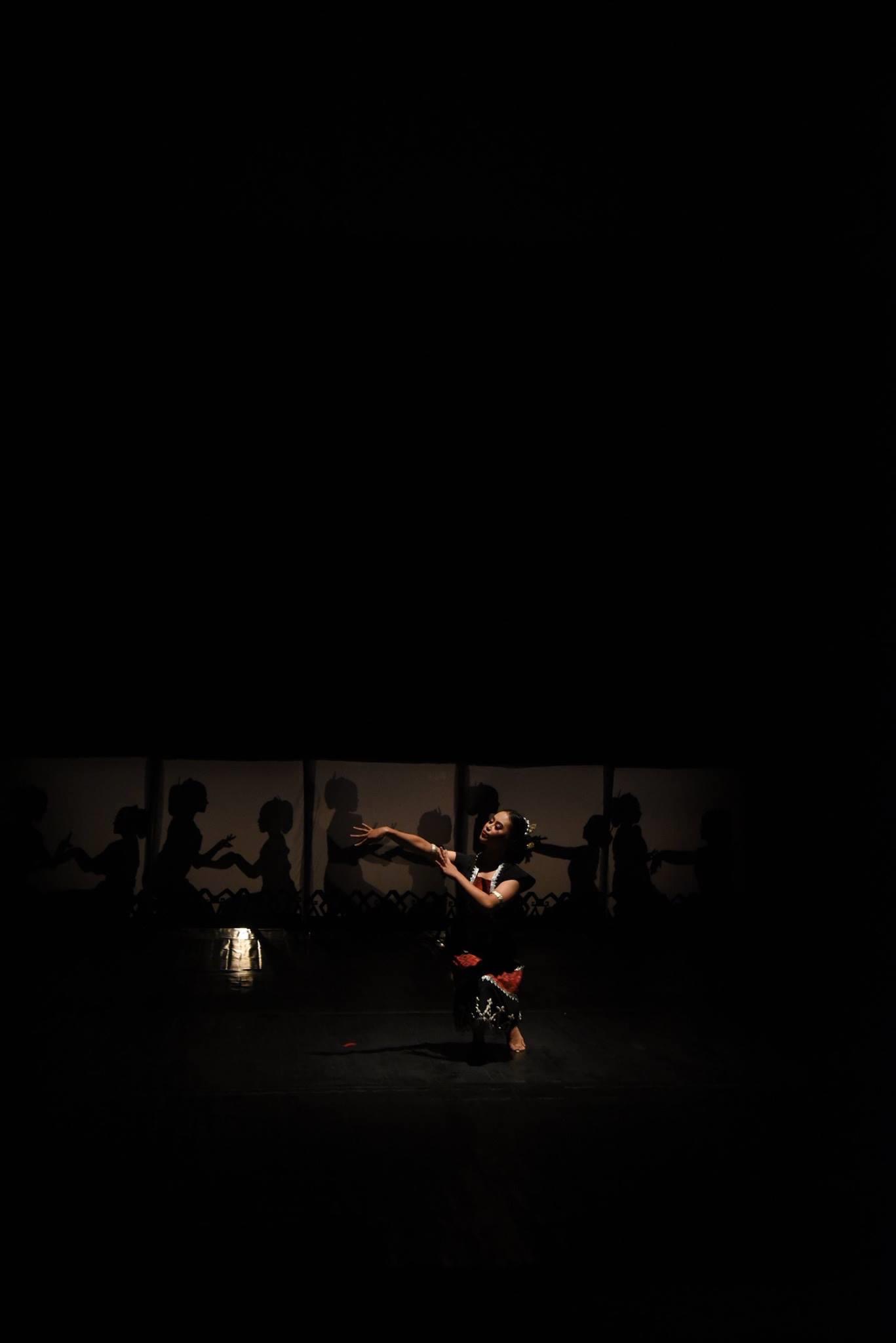

In his choreography, Albert decided to focus on Ibanic women and the process of electing a leader among them. Traditionally, a potential indu’ bantang must first seek another indu’ bantang and greet her at her longhouse with a gift. The indu’ bantang will question the candidate about her skills, and examine how she walks, talks and dresses (traditionally, the shorter the skirt, the higher a woman’s social status). If the indu’ bantang sees potential, the candidate will live with her to learn Ibanic law and to learn how to weave puak kumbu, the sacred cloth used in many events in her community. After she has mastered all the skills, a tattoo called pala tumpa will be engraved onto her hands. The indu’ bantang will then be responsible for taking care of her village—passing judgments in the case of crimes like theft, explaining the law in cases of divorce, or calling for the rain when there is a drought. There can only be one or two indu’ bantang in a village and not all villages have one.

The dance Indu’ Bantang incorporated movement motifs from the puak kumbu weaving. After understanding the main motif, Albert asked us to expand it and develop weaving movements. This piece also gave me the chance to go deeper into the portrayal of an indu’ bantang, to learn and to experience how it feels to be one. Indu’ Bantang is one of my favourite dances because it symbolizes women’s leadership. Plus all the dancers were female and it was great fun to be able to dance with all of my girlfriends and to feel powerful feminine vibes.

The hardest and scariest part of performing this work was when I had to dance on a moving platform. Each of the five platforms were on wheels, with a white screen attached to one of its sides. They were pushed by the male students, but we, the female dancers, kept losing our balance and the boys could not see where they were going. The platforms were also hard to handle because of the weight of the dancers. This frustrated all of us. During our second preview of the work, we messed up the platform section. It was a disaster. Our lecturers were not happy. They disagreed to the use of the platforms and asked Albert to reconsider.

However, Albert demonstrated that he was a strong brave leader, with clear goals. He had been planning on using the platforms for months and believed that we could make it work. He thus decided to risk continue working with them. After months of practicing and arguing, we finally understood the right way to work with the platforms. I found a trick to keep my balance: always stand low, bend my knees a little and place my feet on the edges of the platform to give myself extra support. Our lecturer ended up liking the use of platforms and approved them.

During the production, we also had an example of women’s leadership in the form of our director, a fellow student named Lina. She did a lot for our production, helping the committee members to find ways to settle their problems. During the production process, there was so much work to do and all of us were stressed with our own jobs, so there was a lot of tension and we fought a lot. One day, Lina gathered us all in a big circle and gave everyone the opportunity to confess their feelings and be honest with one another. Some would shout, some would cry, some would give sarcastic remarks while others would pass the blame. Lina remained calm and comforted the ones who were letting out their rage. After this intense scene, everyone fell quiet—maybe they felt relief because they got to let go of feelings they had been keeping in their chests for so long. It was like magic. Everyone would suddenly apologize and hug one another like nothing had happened. With just a simple talking circle, we became friends again. If everyone had continued fighting all the time, the production would have been a complete disaster.

From what I have observed, both Lina and Albert have their own leadership styles. Albert is a very goal orientated leader, confident and truly self-driven to succeed, while Lina tends to lead through communication, focusing on building stronger relationships, helping those who need it and ensuring good team connection. Both styles are effective, but for different situations. Because he is confident with his goals, Albert’s approach can be used to gain a person’s trust. Lina’s approach, on the other hand, can be used to build teamwork and enhance communication between people.

The other challenging part in this project was in delivering the right emotional message. Our lecturers would often tell us that we were not displaying enough emotional depth. Delivering emotions sounds easy, but it was difficult for me. The choreographer wanted to show the elegance of a woman and the firmness of a leader as a very down-to-earth person. I was confused, and we became frustrated since each of our viewpoints were different. Eventually, the other dancers and I found a contemporary dance video on YouTube about lady bosses. The emotional content was just what our choreographer had wanted—a slight smile contrasted with a sharp gaze towards the audience. So we then turned on the music used in Indu’ Bantang and matched our emotions to that from the video. Feeling the music, I started to create a scene in my head where I really was an indu’ bantang. I started to get goosebumps. The other girls felt the same—we knew we had gotten it right.

As a modern woman, I think the indu’ bantang is a good role model that can open everyone’s eyes to the fact that women are capable of doing anything, not only house chores or taking care of the family. The indu’ bantang is not only good at making puak kumbu, she can literally solve every problem in her community. I am inspired to be like an indu’ bantang—a woman who can lead and help a lot of people, a woman with standards, a woman whom everyone respects and admires. Being in this dance made me proud to be a woman and I think it boosted my confidence to want to be a leader. I have always thought that me being a leader was impossible, but the figure of the indu’ bantang gives me the courage to want to try.

A lot of women have the capacity to make great leaders, but they are not given the opportunity just because of their gender. I feel this world needs more women leaders because we are all equal. Gender is not an important qualification for leadership—it is how skillfully and sensitively a person leads the group that matters.

Nurulain Nabihah is a Bachelor of Performing Arts (Dance) student at Sultan Idris Educational University (UPSI). More

To contact the author:

ainbihah911@gmail.com

Featured photo: Angelica Surin @ Rudolf in Indu’ Bantang at Panggung Budaya, Sultan Idris Education University, Tanjung Malim, 21 February 2020. © Malek Sulamin