Independent performer and educator Lim Shin Hui gives an account of one of her recent teaching experiences.

“Yes, yes!” the children yelled. No matter what I asked them, I received no other response. “Yes, yes!” was all they could say.

Teaching creative dance to refugee children from Myanmar was an enormous challenge. Starting from March 2015, I spent a semester teaching at Pusat Kreatif Kanak-Kanak (PKK) Tuanku Bainun, under the guidance of director Janet Pillai. At that point, I was a student in the Bachelor of Performing Arts in Dance program at University of Malaya (UM), and otherwise I had no dance background except some ballet training. At UM, I had attended lectures by Dr. Marcia L. Lloyd from Idaho State University, USA, on the elective subjects of Dance Education and Dance for Children. Dr. Lloyd’s approach convinced me that teaching creative dance should be something fun and interesting, not restricted to any rules, embracing student-centred learning, and oriented towards process instead of product. This experience inspired me to embark on my own learning journey through dance education, to gain more exposure and experience outside of conventional learning environments.

I taught at PKK for eight lessons, to fourteen children from two centres: Zomi Education Centre and PJ Learning Centre. The students’ ages ranged between nine and fifteen. This was my first time teaching children from a different country. Most of the children had difficulties in listening to and understanding English. The older children tended to have a better understanding of English; they were able to listen and respond appropriately. However, a majority of the students could only understand simple vocabulary, and respond with the incessant, “Yes, yes!”, which made me doubt their understanding.

The language barrier became one of my biggest challenges in class. During my first lesson, Chris, a volunteer from one of the centres, worked as my translator. This was my first experience working with a translator, too. He translated and explained very actively, and did a great job in guiding the children’s activity. Unfortunately, a translator can only be of temporary help in solving a language barrier problem, and there was no skilled translator who was able to help during the whole semester of the program. There were a few random volunteers who might have acted as translators, but most of them were the children’s guardians or helpers in the centre, who were working on a voluntary basis without being trained professionally as translators. So we had to figure out a better way to connect and improve on the learning progress of the children.

I believed that body language coupled with extreme facial expressions could be one solution. However, I became extremely exhausted after finishing the first lesson with lots of body language and facial expressions. Then we hit on the idea of an “English-Burmese Dictionary.” This was a piece of mahjong paper stuck to the mirror at the start of every lesson, and filled with important keywords from the day’s learning. The dictionary played an informative role, and enhanced the children’s ability to answer in more detail, rather than with the single word “Yes”. I learned some simple Burmese from the children as well. With this, I had hoped that the children would feel a sense of belonging when they learned and understood in their own language.

These lessons at PKK were probably the students’ first experience of entering a dance studio with a mirror and dance floor. They tended to be very shy and passive, especially the girls. Based on my own observation in the first lesson, I realised that they were more comfortable and confident in imitating movement rather than exploring their own bodies. This actually contradicted the philosophy of the program which was meant to promote creativity, that is, the “ability to process information in order to innovate on the outdated, solve unpredictable problems or create new outcomes”, as mentioned in the handbook Introduction to Alam Kreatif.

To address this problem, I incorporated a variety of games in my lesson plan, to move away from the traditional teaching and learning process. As PKK’s Introduction to Alam Kreatif handbook states, “Good games and exercises make people reflect, feel emotion, bring about a sense of wonder or curiosity, ‘grab people in the gut’, energize, create humour, relax and calm.” Thus, the children were able to learn through playing games, which helped them to warm up and energize their body, to move freely, and to learn about the concepts of dance, for example grouping, timing, rhythm, canon and levels. The children were invigorated, as they could move around doing something new and interesting which also made them happy.

The children were exposed to outdoor activities to experience nature. They walked in bare feet with their eyes covered, hands on a friend’s shoulder, forming a straight line which we called a “tutu train” to explore different pathways around Alam Kreatif. In this activity, they were engaged to be aware of their surroundings with different senses, which included sound, touch and smell. They stepped on small stones along the rough floor, experienced the heat of the floor, felt the windy weather and listened to the leaves dancing to the rhythm of the wind.

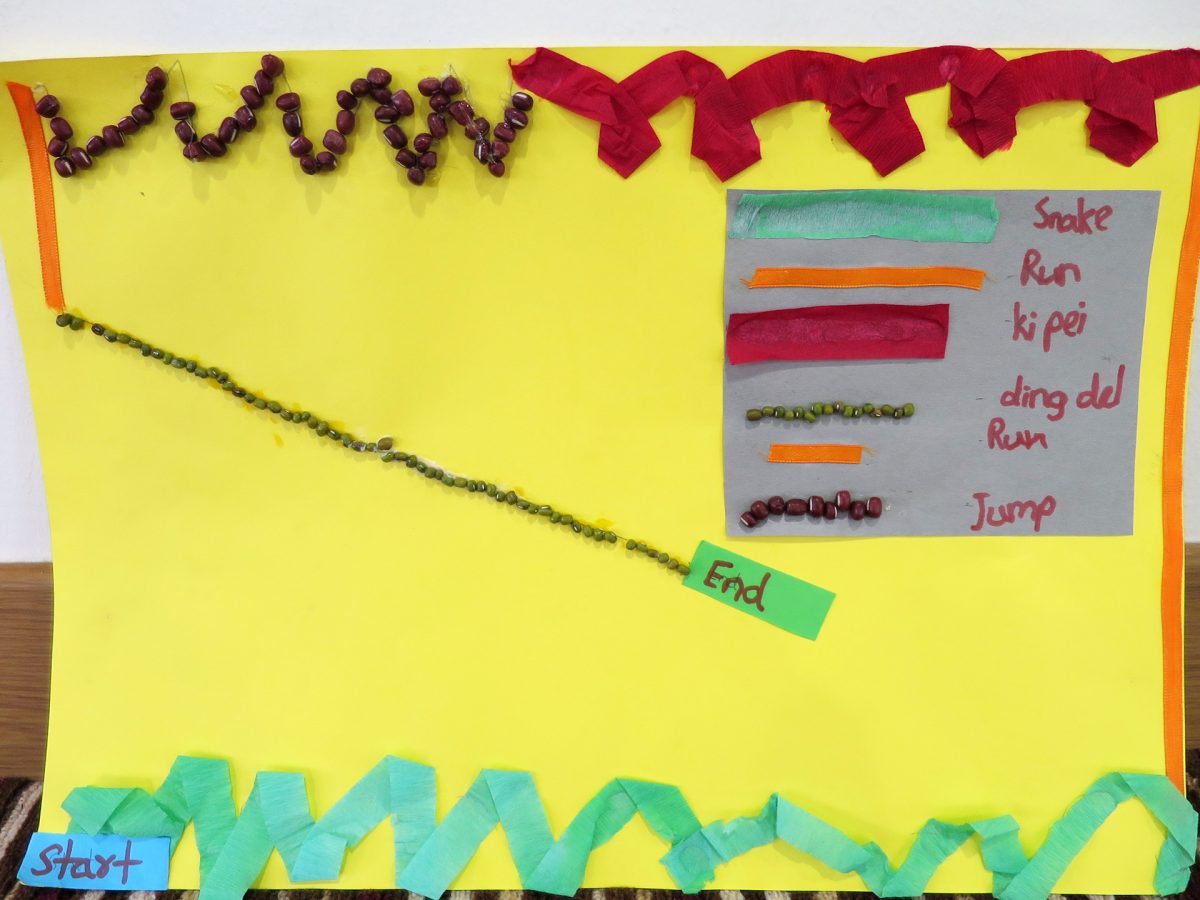

One method I had learned from Dr. Lloyd and incorporated in the classes at PKK, creating dance floor plans, was a good way to integrate dance with arts and craft. The children created their own dance floor plans to encompass what they learnt during the lesson. Firstly, they were given a piece of A3-sized paper on which they drafted their own pathways. Subsequently, they decided on the movements on the pathways, represented by different recycled materials, such as ribbons, red beans, green beans, coloured paper and so on. Methods like drawing, cutting and pasting made the process of learning more effective and enjoyable.

At the end of the semester, the children showcased the creative dance-play they had learned, based on their own dance floor plan creations. The dance floor plans included dance elements like pathways, levels, locomotor and non-locomotor movements, speeds and grouping. The children performed in solos, duets, trios and quartets, starting with a pose on different levels. They also performed according to their own floor plans with various agile movements, and ended with another pose. The dance floor plans culminating in the showcase was such a success, it made me want to shout, “Yes, yes!”

Lim Shin Hui is an independent performer and educator in the performing arts. More

Lim Shin Hui is an independent performer and educator in the performing arts. More

To contact the author:

limshinhui@hotmail.my

Featured photo: English-Burmese dictionary, Pusat Kreatif Kanak-Kanak Tuanku Bainun, Kuala Lumpur, 3 July 2015. © Shin Hui