Mohd Nur Faillul gives a short but detailed account of attempting to incorporate improvisation as part of the choreographic process in a work he did for Jamu 2017.

Faillul’s essay was translated from Bahasa.

“Backbiting” was one of eight choreographic works that was performed as part of the National Academy of Arts, Culture and Heritage, Malaysia (ASWARA)’s Faculty of Dance end of year production Jamu 2017 on 24, 25 and 26 February in the Black Box of ASWARA. As the choreographer of “Backbiting”, I wish to share some of the creative processes involved which left an impact on me.

How Does It Begin?

I began by observing the students who had the potential to present my choreography for about a year, looking at the personalities as well as the antics of Faculty of Dance students in class as well as out. I liked watching those who had brave personalities, confidence, a sense of humour, hyperactivity (genuine, not just put on), open minds as well as unique thinking. I believe the individual who thinks outside the norm is more creative at uncovering ideas, finding alternatives as well as seeing all the possibilities. Through observation, I chose dance students Jeremiah Lim, Nelton Duasik, Emanual Adrian, Fendi Abu Bakar and Azfar Shukri as well as professional dancer Yusof Hasim, music student Mohd Zulfikar and theatre student Akid Jabran. Unfortunately, Yusof was later forced to abandon the production due to a clashing schedule.

Getting to Know Each Other

In our introductory sessions, each dancer told us about the saddest experience in their lives, and subsequently danced a solo to ‘expel’ the feeling of sadness (like the element of trance in main puteri and makyung1both traditional dance-dramas from the Malaysian state of Kelantan). I was interested in Zulfikar and Emanual’s stories. Emanual felt sad because of the death of his beloved grandfather who had looked after him since he was small. Zulfikar felt very disappointed when his scholarship to train to be a pilot was revoked. Yusof did not waste time thinking about sad incidents; he was more interested in the fate of his cohorts who were still unemployed and who had no vision or mission about the development of themselves or their country. The difference in thoughts and experiences of these three participants made them each a unique individual.

Still Improvising

Warm Up

I held warm-up exercises accompanied by random songs. Anyone who wanted to could enter the centre of the studio, and dance according to their own style and feeling based on the song. Whenever the first dancer entered, I would choose a second dancer to dance with the first. Various interesting images were produced. Nelton and Akid created the image of an intertwined snake; Zulfikar and Azfar shifted slowly from the centre of the studio in the direction of the wall clock as if they wanted to transmit a coded message; Azfar and Fendi manipulated a piece of wire as if it was food or some valuable discovery. In this session, I got to know their preferences and likes in improvisation. Conversations and the sharing of stories before beginning the improvisation enabled me to get to know them more deeply, and also generated a comfortable environment, a feeling of curiosity and closer bonds between the performers.

Tasks

Spitting is associated with disgust, filth and the expelling of discomfort from the throat. The first task was to literally explore the action of spitting. The second task was to repeat the first task with the addition of the feeling of sadness or anger. I became interested in a performance in which the dancers moved below the clock on the wall, and the formation was disrupted by Emanual, who was then bullied by his colleagues with the action of spitting at him one by one. In the beginning, Emanual tried to fight back, but then he lost hope. At the same time, the action of Nelton and Zulfikar spitting on their hands, feet and faces also drew my attention.

The performers seemed to find it difficult to manipulate the action of spitting with emotions of anger or sadness. According to them, the literal exploration of spitting was easy because it could be lengthened or exaggerated. But emotion was something subjective. The moments when they waited to see who would spit first were extremely interesting and stimulated many questions in my head.

What They Say about Improvisation

I directed the group in a related task based upon the action of crying. The instructions I gave were quite broad. I reminded myself frequently to be more patient, because the process of improvisation depends upon many possibilities, and the ability to be prepared to fail during any one session. After a few hours of improvisation, the performers became aware that an exploration could evolve and depart from its initial theme. They became more ‘courageous’ to try something new. I felt positive that they were able to release themselves from my instructions. The performers also felt a tightening bond among themselves. Without their knowledge, the improvisation exercises that they had been carrying out slowly improved their relationships alongside developing possibilities for performance through displaying the strengths and weaknesses of each dancer. One of the more interesting discoveries was Malvin producing a very loud noise using only his teeth; Asfar smacking Nelton a few times with consistency; the dancers falling to the floor one by one like fish tossed up on a jetty; and Malvin moving as if he found it extremely difficult to walk forwards.

I See Their Other Dimensions

I instructed the group in a task that I had learned from the German choreographer Arco Renz, to find five interesting objects in the studio and to create a performance using an arrangement of those objects. Many unforeseen events occurred. Yusof presented an interested scene using lip syncing. He wrapped his body in the kneeling position of prayer upon a long bench, using a curtain. The large size of the fabric created an exciting atmosphere which also raised all sorts of questions. Yusof also manipulated his mobile phone. We as the audience were full of questions and never lost interest in his performance from beginning to end. The combination in Yusof’s performance of personality, object choice and arrangement was extremely effective. Yusof is a talented improviser who possesses a rare appeal.

I was also interested in the exploration of Jeremiah and Azfar. Although Azfar is shy, he was able to create an explorative performance with courage and confidence. He used a bench and a few chairs as props. I felt pleased because he did not exhibit any apprehension, and was even able to look us all in the eye. I don’t know what ‘possessed’ Azfar in that moment. Jeremiah too is not one of the most outgoing students in a class. However, I was surprised to see him able to conduct an emotional journey among the audience from start to finish. He covered his head with a bucket and that was enough to raise thousands of questions from our midst. In addition, Jeremiah’s movements which were weird but interesting added to the delight of the exploration. I experienced Jeremiah’s exploration like that of a magician’, full of mystery.

The Parrot Speaks

Jonathan Burrows in his book A Choreographer’s Handbook says that the feelings of doubt and too much judgment in the process of creating choreography is like the whispering of a parrot sitting on your shoulder. There are times when Burrows listens to its advice, and times when he doesn’t. I like this metaphor because every choreography faces deadline pressures (the day of the performance) and needs to take into account the reactions from the audience.

In the beginning, I was very worried that this choreography would not be finished in time because of scheduling conflicts with the busy students. But at the end, I faced the problem of having too much choreography, going way over the allotted time (10 to 12 minutes). I was forced to make choices, although I was unwilling to sacrifice parts of the choreography. I also felt worried that I had chosen the wrong music, or too much music. In the end, I resolved to use four short music excerpts.

My dancers did not have perfect physical technique because I had chosen them based on their personalities. As the choreographer, I wanted to highlight their strengths and to find uniform movements that were appropriate to their abilities. As suspected, I spent the most time working on the second section, which consisted of ‘pure movement’. These four minutes did not employ complex floor patterns or composition, but they needed to be performed with confidence and uniformity. Enormous effort and patience were required so that they could carry out the movements with the same energy and focus.

When Choreography Begins

The final choreographic process only started about three weeks before the performance. Again, I felt anxious about arranging the framework of the choreography according to the theme based on a selection of movement material from the improvisations.

I had particular difficulty framing the duet between Fendi and Azfar. In the beginning, I wanted to set each movement according to lyrics that I created, but it didn’t work out. After receiving advice from fellow faculty member Datin Marion D’Cruz, I was thankful for the idea to base the duet upon a recitation of a text (a voice recording by Marie Dubuque). I finished the duet in two hours.

At first, I divided the choreography into four sections. However, I changed the compositional structure after receiving feedback from Datin Marion D’Cruz during the preview session. The duet which featured the text recitation was turned into the opening so that the audience would quickly understand the thematic content of the work. The second section was the pure movement dance performed in synchrony. The subsequent part was a quiet section that showed the action of spitting as a symbol of filth, highlighting Azfar as the main character who presents a feeling of stress and anxiety. Finally, all the dancers stood in a line and moved with minimal movements to the song “Evil Woman”.

Watching the choreography of “Backbiting” again, I am pleased that all the dancers became intimate with each other through the method of choreography that I had learned from Michael Keegan-Dolan while I was in Ireland. The positive impact could be seen from the chemistry that was created among the performers. They felt extremely comfortable on stage together, although they came from different years and different disciplines. I was thankful that the choreography was fruitful and received positive feedback. However, I most enjoyed the moments, memories and encounters that were acquired during the process. As a choreographer, not only did I learn something about choreography, but I also got to know the performers, and grew to appreciate the knowledge about human relationships generated by the process that I had adopted.

Mohd Nur Faillul is a lecturer at at the Faculty of Dance, National Academy of Arts, Culture and Heritage, Malaysia (ASWARA). More

To contact the author:

failluladam@gmail.com

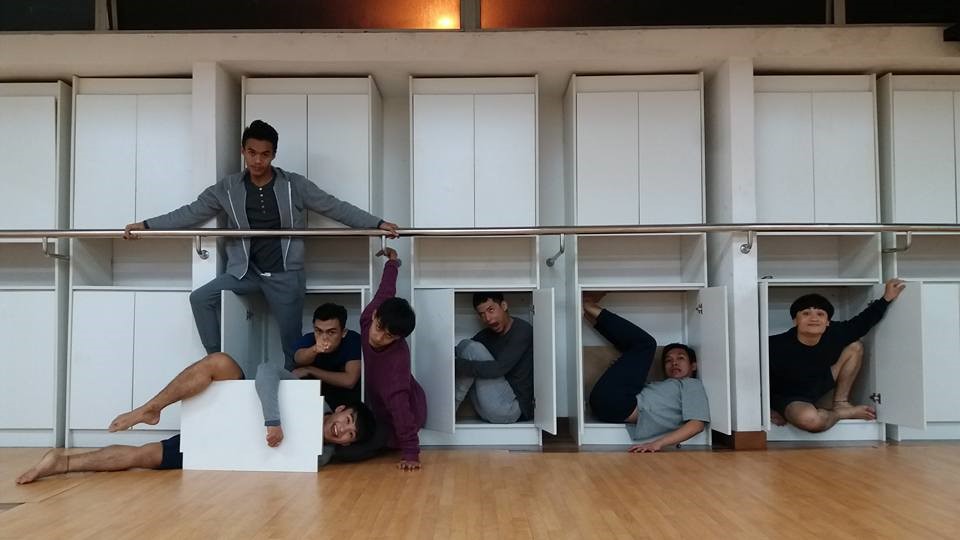

Featured photo: Mohd Zulfikar, Nelton Duasik, Emanual Adrian, Azfar Shukri,

Jeremiah Lim, Fendi Abu Bakar, Akid Jabran in Studio Tari 4, ASWARA, Kuala Lumpur, 2017.